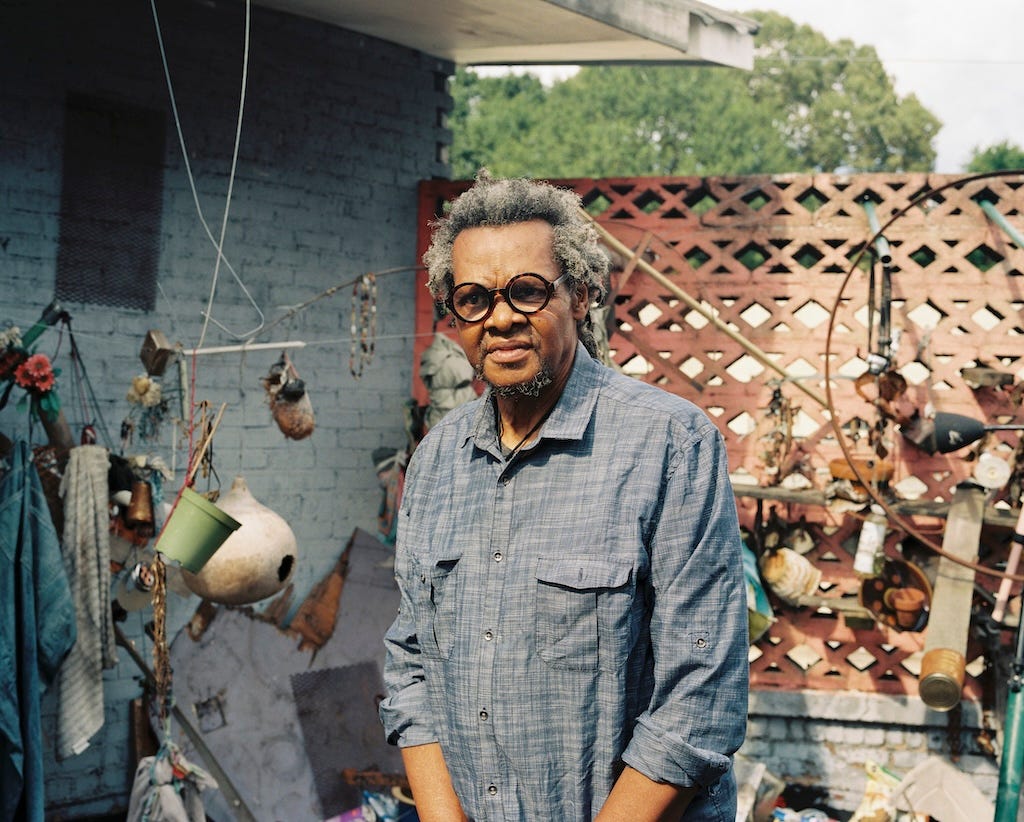

This week, Atlanta-based artist Lonnie Holley joined me on Aquarium Drunkard Transmissions ahead of his new LP, Tonky. Crafted with Irish producer Jacknife Lee (R.E.M., U2, The Killers) and featuring guests like Isaac Brock of Modest Mouse, harpist Mary Lattimore, rappers Billy Woods and Open Mike Eagle, spoken word from Saul Williams, and others, Tonky rattles with blues-punk-industrial art folk anthems. We discussed the new album, Holley’s poetic metaphysics, and his work with kindred spirit Richard Swift.

Listen to our talk wherever you get podcasts via our partnership with the Talkhouse Podcast Network

I first encountered Holley in person in Marfa, Texas, where we performed as part of the Marfa Myths festival. We spoke then, and it was a beautiful conversation about close listening and “thought-smithing,” Holley’s preferred term for how he creates both physical art and music. When I last encountered him, it was at an oracular show in the Cibo Carriage House in downtown Phoenix, entirely and brilliantly improvised, as is Holley’s standard practice live and in the studio.

But my very first encounter with him was in August, 2013, when I interviewed him for the alt-weekly Phoenix New Times in advance of his opening slot with Deerhunter at the Crescent Ballroom. That first conversation remains really dear to me. As a fan of the prophetic science fiction of Philip K. Dick, who said, “The symbols of the divine show up in our world initially at the trash stratum,” I’ve always found Holley’s art—made initially with actual trash–a beautiful manifestation of that idea. “To this day, I would say that I’m most at home in the grit, finding what’s called trash,” he told K. Leander Williams. So let’s go digging with this archival 2013 interview, centered around his essential Dust-To-Digital release, Keeping a Record of It.

Originally published at Phoenix New Times

Lonnie Holley's art begins with troubled times.

The 63-year-old's first artistic project was carving headstones for his sister's two children, who died in a house fire in Alabama in 1979. Since then, his found-object assemblages, paintings, and collages have endeared him to the fine art world—they have even been displayed in the Smithsonian and the White House—in part due to the patronage and care of Atlanta art collector and historian Bill Arnett.

He's always sung, too, recording crude cassettes full of impressionistic melodies. In recent years, Matt Arnett, Bill's son, has helped expose Holley's musical work. In 2012, Georgia folk label Dust-to-Digital released Just Before Music, featuring Holley's first professional recordings, and on September 3, the label will release Keeping a Record of It, a new album featuring contributions from Deerhunter's Bradford Cox and Cole Alexander of The Black Lips.

With its repetitive loops and free stretches of melody, Holley's music is often placed in "outsider" or "avant-garde" contexts. But at its core, Holley's music is folk music, and his chief concern is expressing the relationship of humans to their art.

"In a sense the record has a lot of offerings being made toward the ways of life," Holley explains over the phone from Atlanta, having just finished a pastry and iced coffee at Octane Coffee/Little Tart Bakeshop with Arnett. "What I mean by that is our ways of life as humans; how that information gets to us. A lot of times we've been respecting art and music [in terms of] 'What kind of music is this or that? Does it fit into the African American category, was it something that was done back in the days when we were called black, or colored, or even back in the days when we were called the Negros in America? Was it spiritual or was it just for the human's relaxation?' I try to bring a little bit of all of that in Keeping a Record of It, in exposing something that is necessary for the better understanding of us."

It was during car rides with Holley that Arnett realized the necessity of professionally recording the artist.

"We would be traveling, and he would always get in the car with some kind of homemade tape that he had been working on," Arnett explains. "Something he'd been working on in his studio, cobbling together tape decks...In 2002, I spent some of the summer recording a cappella gospel music in Gee's Bend, Alabama—where the world-famous quilts were made. I went back in 2006 and set up a recording studio in an old church, and did much more organized recordings. I took Lonnie, and we recorded him in the evenings."

Like Holley's visual art, the recordings, which eventually saw release as Just Before Music, didn't easily fit in any mold. But an email exchange between Arnett and his friend, Samantha Parton, of folk trio the Be Good Tanyas helped define—however loosely—Holley's music.

"Not that I don't think Lonnie's music is completely its own thing, it definitely is," she wrote. "But he's also kinda like John Coltrane + Gil-Scott Heron + Bukka White + Olu Dara + Jimi Hendrix all rolled into one..."

The quote makes sense: Keeping a Record of It, doesn't conform to conventional song form any more than Holley's art conforms to traditional standards. Holley makes "free" music, but there are traditions at work in his voice. He employs jazz, folk, and blues idioms at will, but stretches and contorts them into singular expressions.

The record is named for the piece that adorns its cover, a small animal skull placed on a turntable, and the music is as fragmented and hauntingly beautiful as the image: "Six Space Shuttles and 144000 Elephants" describes a dream, and Holley's voice is pure expression. The title track, recorded outdoors with Cox and Alexander, celebrates spontaneous creativity. There are more recordings from Gee's Bend Church, and a powerful spiritual feel throughout. But while Holley's music has a catholic quality, songs like "From the Other Side of the Pulpit" are unafraid to address Holley's concerns as an "outsider."

"I always was singing," Holley says. "When I'd go to church with my grandma and my mama...if I tried to get up during the testimony period or during the period when we could sing, that had to be controlled. That's why I did this piece, 'On the Other Side of the Pulpit.' It actually was a piece of music that was put together about things that are occurring outside of the church doors, outside of the institutions, outside of the schools, the colleges. Outside of the control...this music was made on the other side of all of this."

He credits the Arnetts for recognizing the value in his work, with little regard for qualifications other than the work's emotional and spiritual impact.

"What it's about," Holley explains, "is bringing the truth to the surface."

Watching/Reading/Listening

Practical Magick: Ancient Tradition and Modern Practice, Mitch Horowitz

The Crusaders, Pass The Plate

Dennis Wilson, Pacific Ocean Blue

Dean Wareham, That’s The Price of Loving Me

this was great. Wouldn't have heard of Holley otherwise and excited to dig in.