This is a big week for Phoenix ambient fans. On January 17-18th, Arizona State University’s west campus is hosting Super Bloom, a free drone festival headlined by Claire Rousay and Steve Roach at the Kiva Lecture Hall.

The moment the show popped up on my feed during that indeterminate stretch between Christmas and New Year’s, I put it on my calendar. I caught Roach at Tucson’s Hotel Congress last year my brother Alex, not long after he appeared as my guest on the Aquarium Drunkard Transmissions podcast, and I’ve been thinking about his immersive sound worlds ever since, longing to take another dip. Give how franticly this year’s started out, I’m more than ready that return visit to the sound current.

Roach has been releasing music since 1982’s Now, and his vast discography encompasses all manner of longform drift: Berlin School electronics, didgeridoo-led tribal trance, and even a nascent entry in the “ambient country” field. In addition to a steady sequence of new recordings—Roach is the ambient equivalent of Guided By Voices, “prolific” hardly does his output justice—last year saw a remastered 40th anniversary version of his classic 1984 album ambient landmark Structures From Silence, and a high-definition edition of 1988’s Dreamtime Return, both favorites of mine.

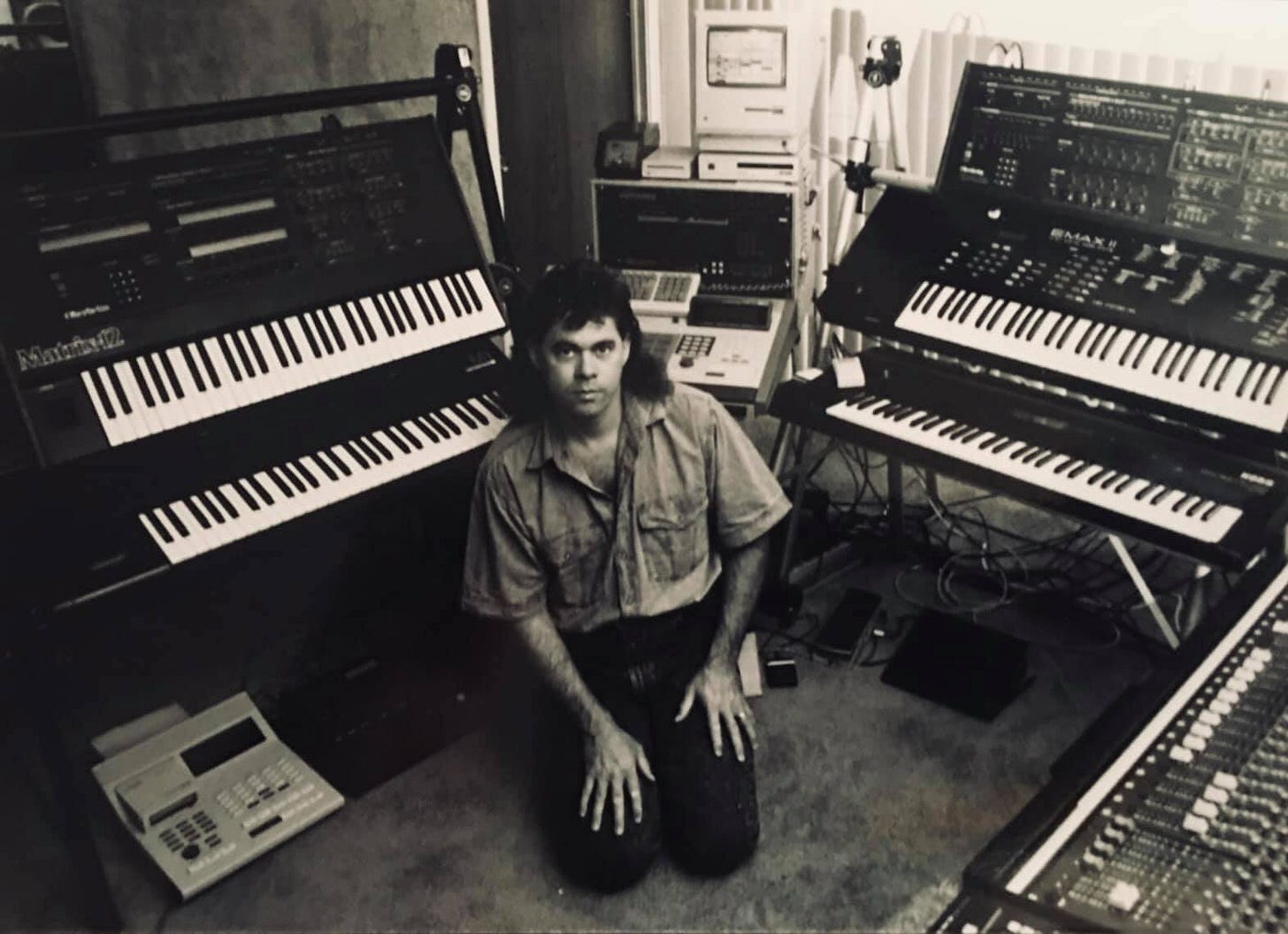

Few sound artists draw from the desert environs as deeply as Roach does. In the early ‘90s, he moved to Arizona, situating his studio—a small flat packed floor-to-ceiling with synthesizers and equipment called the Timeroom—on a rocky bluff south of Tucson, just north of the Mexico border. “Using music as a powerful tool for consciousness? I'm all about that,” Roach told me when I interviewed him there for a feature called Celebrating the Silences, which was published by the Tucson Weekly in 2014.

To get us all ready for Super Bloom and evoke that desert power mindset, I’m presenting an excerpt from an extended interview segment that ran as a supplemental to the full story. We start, as one normally does with ambient pioneers, by talking about very fast cars.

I understand that you drove race cars in your youth?

Steve Roach: Growing up in Southern California in that era of the ‘70s—the whole spawn of the baby boomer wave—motocross was really kind of born in southern California. I was right where it was all emerging. If I wasn’t out hiking in the desert I really embraced this sport that was right in our backyard. It wasn’t as incongruent [with music] as you would think, because there’s a real kind of discipline you have to have. If you’re going to do it, you have to be fully awake and present. Your life depends on it. You’re completely in. You’re inside of it. That set the tone.

That makes sense in relation to your music.

The thing that really shaped me in that time was a lot of time spent in the deserts outside of San Diego. Just in quiet, in silence, [listening to] desert sounds, the sound of the space itself. Tuning into that. My parents introduced me to that whole world before I could drive. We’d go out desert camping, that sort of thing. We’d go out into the mountains of San Diego and to the ocean. So later on when I was able to start driving myself to these places, I might start out in the mountains midday and watch the sunset at the ocean. Those kinds of landscapes and atmospheric dynamics set the tone early on for me as an artist in terms of the kinds of spaces I wanted to be in and draw from.

What were you listening to then?

A lot of European music: Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Amon Düül, Popol Vuh. All that sort of music that had grown out of the sixties’ experimentation. There was a real psychedelic quality to it. I was drawn to the more progressive stuff, Pink Floyd and Yes, but that music still felt pretty tethered down to the ground. I wanted something that was more expansive, that started moving beyond your perception of time. That’s when I discovered Timewind by Klaus Schulze, with 30-minute songs on both sides

Your first two records, Now and Traveler show that German space music influence most clearly.

With Now and Traveler I made a conscious decision: I wanted to create shorter pieces. Rather than do these 30-minute sides, I wanted to create songs that were like stops on a road—like Tucson, on to Phoenix, on to San Diego, to Santa Barbara, to San Francisco, to Portland and on to Vancouver. I wanted to that feeling of a journey across an album.

After making albums that focused on shorter pieces, you shifted into longform composition with Structures from Silence in 1984.

Yeah. Early into my career, I was making deliberate choices about doing shorter pieces, and then here comes [title track] “Structures from Silence.” It has no references to anything I had been listening to from Europe. It wasn’t the repetitive sequencer-style stuff we’d been hearing from Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk and all that. Structures is where influence of my environment really took over in my work—[tapping into] the space you find yourself in when you’re in the desert and time slows down, your sense of awareness gets expands and is magnified. That sort of thing was very consciously coming into the music. I was making drives from Los Angeles—where I’d moved to do electronic music—to Joshua Tree, and then bringing that feeling back.

Your music quickly became associated with the new age musical movement. Were you thinking about composing music for meditation or healing? Were you considering applications for your recordings, or were you more interested in tone?

I guess you could say I “composed” the music, but really I’m in the room with these instruments, playing and responding and creating something, and it’s really…I keep going back to painting. When you’re painting you look at it from different angles, and observe the way the light changes through the day. All that stuff influences the piece.

Structures was the point where that whole space was born out of me, brought into form. The first piece, “Reflections in Suspension,” that was recorded completely live, directly to two-track with no overdubs. You’re hearing it as it’s occurring. It’s like taking a photograph, like Ansel Adams or something—you’re photographing a moment, and when you look at it you’re transported to that exact moment in time. It’s not like I was looking at it saying, “If I add a little bit more of this delicate harp-like sound with delay it’ll really fit into that healing component for the new age genre.”But then there’s the other side, the healing nature of music, and that’s completely valid and important.

[That’s] using music as a powerful tool for consciousness. I’m all about that. Your body can become almost a tuning fork, tuned to certain emotions, openings, and feelings that you get from sound. If you’re tuned that, that music is going to start to find its way out into those places in the world.

And it did naturally. Many letters came in from families that were using Structures in hospice programs for people moving on, and for children being born. You’ve got both ends of the spectrum, and between that you’ve got people using it to slow things down—breathing, yoga, things like that. So much of what I do becomes a tool, but the core origin of it all is me wanting to create these resonant sonic spaces I can live in, extracting some essence you get from nature, putting it under a microscope, and blowing it up on a big 70-millimeter screen.