Author, speaker, and TV host Mitch Horowitz knows a thing or two about synchronicity. Last year, he hosted his first ever podcast for Spectrevision, Extraordinary Evidence: ESP Is Real. A deep dive both data-driven and uniquely personal, the show offered an exploration of, among other outré topics, clinical studies of global “universal consciousness” that found people remembering staggering details about potential past lives. We’re talking about the kind of synchronicities that light up the part of our brain that says, that’s something. As a seeker, Horowitz chases that something.

This week, Horowitz released his latest book, Practical Magick: Ancient Tradition and Modern Practice. Like a few of his previous titles, such as the overview Modern Occultism: History, Theory, and Practice and the essay collection Daydream Believer: Unlocking the Ultimate Power of Your Mind, the new book falls somewhere between the two sides of Horowitz’s output: the more straight-up “historical” approach of books like Occult America and Horowitz’s self-help manuals, such as The Miracle Habits. Pulling a little from column A and a little from column B, Horowitz argues in favor of a Jack Parsons-inspired simplified approach to “magick,” a kind of workaday metaphysics.

I especially enjoy having Mitch on my podcast, Transmissions for Aquarium Drunkard. He’s been on four different episodes, each one is a blast. But this talk is a little different, being print-based and all. But it’s just as riveting as those other appearances. But before I share it, I wanted to note a particularly wonderful synchronicity. It’s easy to long for the old days, when geniuses of paranormal entertainment like Art Bell held court over the airwaves, but you’d never experience an exchange like this on vintage Coast to Coast: While hosting Mitch for a live online interview on his weekly Podcraft, Wu-Tang member Killah Priest cuts his mic to take a call—mid broadcast. And no big deal, it’s just Ghostface Killah (aka Tony Starks) on the line, ringing in to talk about a new city they found under the pyramids and aliens under the ocean. Right after co-host AD made an Iron Man reference. Best Wu-Tang podcast moment of the year as far as I’m concerned. Anyway, let’s get into it, Mitch Horowitz on magick, comics, and the power of silence.

Jason P. Woodbury: Speaking of interviews, I listened to it, but I saw that I could have watched your talk with Pam [Grossman of The Witch Wave].

Mitch Horowitz: Yeah. It’s terrific. Thank you. She's starting the video podcasting aspect of The Witch Wave right now. It’s still very much a maiden voyage, but I was really glad we did it. The tech quality was great and of course the rapport speaks for itself.

JPW: I'm a big fan of her show. She's got a Ms. Rogers vibe, very comforting and gentle, but not dull either.

Mitch Horowitz: She humanizes so much and she's so funny. In fact, I would say even off-camera, she's so hilarious. I mean she'll just say and do things that are just hysterically funny.

JPW: Congrats on yet another book.

Mitch Horowitz: Thank you. When I started the damn thing, I thought I was out of steam. I didn't know how I could do it. In fact, I was at times really sitting down, maybe meditating, and then coming out of meditation, and saying to myself, “What the fuck am I going to do?” And I realized at a certain juncture that I needed to bust up the structure that I was using. The book is based originally on a class that I did with The Theosophical Society, and it was six long chapters, mirroring the six class sessions.

And I realized that that structure that had worked well in class form was killing me in book form. It just wasn't the nature of the material. And also, as you are probably aware, massaging, editing, and revising transcripts into written word is arduous. In fact, it's almost better to rip it up and start again. Naturally spoken word and written word have great differences in cadence.

The written word that emerges from the transcript, even though everything rang out with such clear resonance during the talk or the class or what have you, seems very barren and disjointed—even the syntax seems off. I decided I had to throw away the transcript, start entirely from scratch, get away from the structure of six chapters, open it up, let the subject matter fall into its own slots, and then it sang, then it came together. But for a few weeks there, I was not sure I had it in me to do this book. I was concerned but I took a big left turn and I got home.

JPW: Having taken classes with you, I know how eloquent and conversational you are, but it’s the sort of thing that requires a willingness to toss out the plan if the plan is not yielding the results.

Mitch Horowitz: It had to happen. If I could, I wish I could turn the clock back to 1902 when William James was writing his Varieties of Religious Experience, because that book itself is based on a series of lectures, the Gifford Lectures, that he delivered at Harvard. I would love to know the process of a master like that. Whether he wrote out his lectures and stood there and delivered them like a formal paper, or whether he just spoke from notes and then had to undertake the process of writing the book from those notes. I've known a couple of other authors who are also dead, who produced books from lectures, and I just don't know whether they read a paper in front of a group of people, which I find stultifyingly boring and I attempt never to do, or whether they had to start all over.

Spoken word precedes written word, and that's true in human history. That's true in the development of the human animal. And yet they’re such different mediums. I have had the experience previously. For example, Modern Occultism started out as a 12-part class, and there too, I began to transform the transcript into the chapter, and past a certain point, it became counterproductive. It was actually easier, better, more satisfying to just throw the damn thing out. It's the thing we're most afraid to do because we perceive the transcript as guardrails, but in fact, it really can be a barrier.

JPW: There’s a great part of the book where you're breaking down these folkloric things that are commonplace: a rabbit's foot; knocking on wood and sharing rules of luck. We've all heard of those things or done those things, you invest the actual time to trace their lineage, where that stuff comes from, why those things happen. I just thought that was a brilliant chapter, but also it's a very short chapter. It's like a beautiful little digression, not sure that’s the right word. That the book feels almost like your most footloose and fancy free in a strange way.

Mitch Horowitz: Which by the way, I think is a very good Rod Stewart album. I think the critics are wrong. Maybe we could do a revival of Footloose and Fancy Free over at Aquarium Drunkard.

JPW: I mean, we're a more Faces-focused thing. But yeah. [Laughs]

Mitch Horowitz: [Laughs] No, I understand. I'm heterodox when it comes to Rod Stewart. He sang "I Ain't Superstitious” but like many people, superstition is my guilty passion, we'll say. Certainly Franklin Roosevelt did not need to carry a lucky rabbit's foot, and yet he took it seriously enough so that he was never without it on his first presidential campaign, then gave it to a trusted friend to hang on for his next campaign so it wouldn't get lost. I'm the same way. Everything I write about I do and I participate in. I have my reasons for it, some of which maybe can be described as just abiding reminders of humility, like a knock on wood or something of that nature. We as human beings strike some strange bargains with the natural world. I get very attached to and very affectionate towards some of those bargains.

They attach us to some of the really old ways that our ancestors might have abided or practiced. I'm just thrilled to discover remnants of ancient occult practice in our world. For example, I think I briefly mentioned this, the traditional Western wedding ceremony very closely mirrors ancient Roman practices. In fact, the bridesmaid dresses themselves are a device from ancient Roman practice to distract evil spirits from the bride. So her friends dress up in similar dresses, formal, and they confuse the bad guys. And lo and behold, here in the 21st century, we still do it. Nobody knows why. Everybody's angry, “Oh, I have to buy a bridesmaid dress. I'm only going to wear it once.” But if you could remind people that this takes us back to the ancients, it imbues it with a little more meaning than just conformity or custom.

JPW: I first read your book Occult America, in which you trace underexposed or considered connections to these traditions that are nonetheless deeply embedded in our society, culture, iconography, and all around us. You cite the song “Iko Iko” in the foreword. Could you reflect on your use of that song?

Mitch Horowitz: I had been aware of the song for many years, and it came back to my attention recently because Jacqueline Castel and I were watching a very good and underrated supernatural thriller called The Skeleton Key, which takes place in New Orleans. And one of the characters in the movie is listening to the original Dixie Cups’ 1964 recording of “Iko, Iko.” It sounds very haunting, because it is haunting. When I started to dig into the song, I was shocked that this Top 10 song was recorded by young women who themselves had been, just because of where they grew up, steeped in hoodoo and voodoo tradition.

It strikes my ears that it's all percussion. One of the artists said [paraphrasing] “You bet. It's all percussion. We were just sitting in the studio messing around, and somebody started banging on Coke bottles and this, that, and the other thing, and the damn thing became a top 10 hit.” That song is almost like a hoodoo anthem. I realize it's about Mardi Gras parades in New Orleans, but the West African rhythms and the Nigerian soundscapes, the nature of the lyrics—it’s just a piece of folk art.

It sits so well within hoodoo tradition. I was so haunted by the song. I do spend a little time in the book on hoodoo, and it seemed to me to be a capsule of magic that survived the Middle Passage journeyed from Nigeria, west Africa, central Africa, to Afro-Caribbean nations to the American South, and it's the closest that we have to a magical hymn in a certain way in our popular culture. I was enchanted with it. I couldn't stop thinking about it. So I guess for impressionistic reasons, I just decided to open with it.

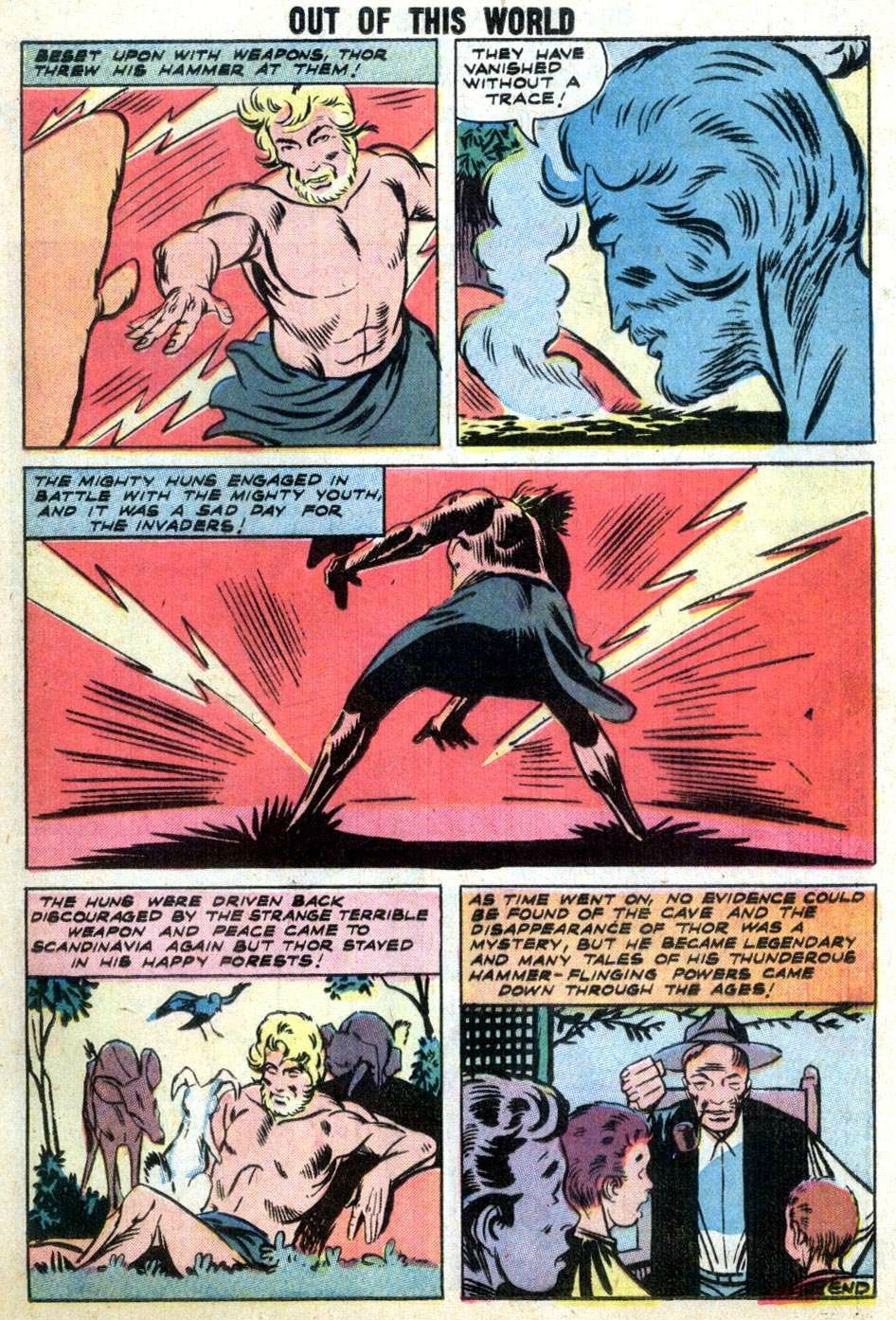

JPW: You return at one point to a familiar topic of yours, comics artist Steve Ditko. I know how much you love his work and I do too. Not his politics so much, but his work. I have always been interested in the paranormal, the New Age, and weirder stuff, but it was reading Mutants and Mystics by Jeff Kripal that really fired up my imagination and drew me deeper into all this stuff. Due to my personal interests in comic books, science fiction, pop culture, those things, it possessed a crazy resonance to realize the way the esoteric and the occult finds purchase in modern life through fiction, pop fiction, pulp fiction, etc. Realizing “The Phoenix Saga” from the X-Men books was essentially a kabbalistic parable, you’re struck by these ancient ideas, they don't necessarily go away. They transmute. They reach us in other forms.

Mitch Horowitz: No question. I mean, Jeff's insight was that the stories of the gods populate our comic books not only in this kind of shadow of culture, or this retentive nature of culture, but he in fact sees it in a very literalistic way, a very actual way. These powers are not just some figment of storytelling, but they're part of the human tapestry. They reverse the human situation, the extra-physical situation, the situation of deity or gods, and we digest them in these acceptable forms through X-Men or Dr. Strange or The Incredible Hulk, or you name it, and all of this stuff. It's amazing. I love the congruity of all of it.

JPW: One of the things that you've written about regarding Steve Ditko is his willingness to work for less reputable comic publishers in exchange for no editorial interference or creative restrictions. And that was comics in general, a low form, comics were on the lowbrow trash side of publishing. And that's where these ideas sort of take root and then find us now in modern day. Think about Thor. How many people know the “idea” of Thor? An ancient deity should be so lucky.

Mitch Horowitz: Right, I know. It is only very recently that we've witnessed comic books suddenly go from this unwashed childish junk medium to being on display in galleries. Thinking about Steve struggling to pay the rent at his Times Square studio, and this time that nobody gave a shit about what he was doing or who he was. I recall vividly, even as a little kid when I was collecting comics as a kid, my friends and I, I'm ashamed to say, we regarded Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby as guys who belonged to yesterday. It was childish. The lack of realism bothered us. We liked John Byrne and Neil Adams, and then later, Frank Miller. Steve and Jack seemed like just weird uncles trapped up in the attic.

Now of course, I look at them and it's astonishing. It's jaw dropping, it's inspiring. And Steve's career has been so inspiring to me because he charted that independent course. I don't know whether it's true, but it certainly fits the character that Steve was offered and turned down money from the Dr. Strange and Spider-Man movies. He didn't like the movie treatments, didn't like the stories. It’s very Steve. Before he died, I wrote to his publishing partner Robin Snyder. I asked if I could briefly interview Steve and was told something to the effect of, “Steve could not possibly talk to you.”

It’s alien to me because Steve did not seek attention. And I certainly can't say that for myself. I do seek attention and I don't fully understand the personality of the man who doesn't seek attention. So that only deepens my sense of wonder at Steve. He's almost like an Orson Welles or a Howard Hughes or a Bob Dylan. Who is this guy? It's very interesting.

JPW: I especially enjoyed the chapter on silence. It’s such a rare thing these days. With music, YouTube videos, podcasts, all this stuff vying for our attention, it’s nonstop. But silence is so worth contemplating, in its multiple forms. I’m dancing around this, so I’ll just say it: how many times have I told somebody about a creative project that I want to do, and then I go on to never actually do it? It’s like telling that person tricked my brain into thinking that talking about my brilliant idea was just as good as actually doing it. So I’m reflecting a lot on how silence is a tool to be held and refined and used for our benefit.

Mitch Horowitz: I really dig hearing that. Silence has always been one of the cardinal laws of occultism, but nobody knows why. We all tell ourselves, keep your spellwork to yourself. Talking dilutes things. That's what we do in therapy. We take the thing that happened to us in life—“Somebody looked at me funny”—and we expound on it. So I go and I bore the shit out of my therapist, who has no choice but to listen, or we bother our friends or whatever.

Sometimes, in fact, these things need to be aired. They need to be diluted, they need to be sounded. I don't think a person needs to be morbidly disclosing, and I don't think repetition has any therapeutic benefit or tonic, but talking something over with an intelligent peer colleague, whomever, that can be really necessary.

That provides a hint to why silence is powerful: because it doesn't dilute the idea. When that idea is diluted, we lose a sense of agency over it. We lose a sense of productivity around it. And furthermore, there is a pretty good chance that the person we're talking to is going to wrinkle his nose or run it down or do something because people like to attack things that they feel is out of reach.

If something feels out of reach to them, it may not be out of reach to you. And they're liable to say, “Oh, but didn't so and so do that?” And it's like, I don't give a shit whether so-and-so did it. I don't give a shit whether somebody else used the title The Tarot before. I just don't care. The point is the individual who does it well, who does it right. Or that he or she owns [the work] conceptually. Silence is so important. Silence is so important. And just not about things that are intimate to us, but politics and social issues. I can rattle off something I read somewhere and pretend to know a fact about the Constitution, but that gets you found out.

I can tell in an instant when people talk about books that are valuable to me, and they haven't read them—a book like Madame Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine or Beelzebub's Tales to His Grandson by G. I. Gurdjieff. I'm like the middle school teacher who always knows who hasn't read Animal Farm. I can fucking tell you! I've seen people, writers, well-known successful writers, make references to texts like that. I'm like, “They haven't read it.” So I should be at least as stringent with myself about things that I haven't firsthand researched, read about, nailed down. And so big deal. I'll talk 10% less. The world will be better for it. I'll be better for it.

Great conversation! I thought I was the only one who knew the Dixie Cups sang Iko Iko, but I never understood it! Thanks for the explanation.

Synchronicity. Silence. Such awesome topics. I need to meditate on it!